Stock-Based Compensation: Investing’s Latest Scapegoat

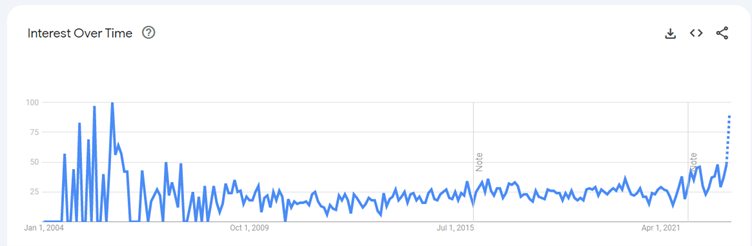

Rabbit holes are for rabbits. The current burrow du jour is stock-based compensation (SBC for cool dudes) – more people are Googling the term now than at any time since the dotcom bubble. Perhaps this isn’t surprising given the sell-off we’ve seen in high growth tech stocks since 2021. Where can respectable quality growth investors point the finger, if not at those greedy, long-haired CEOs reclining on beanbags in their Nassau megapads, blowing our hard-earned cash somewhere in the metaverse?

Figure 1: More people are Googling ‘stock based compensation’ now than at any time since the dotcom bubble

SBC vs SBF – Which is Worse?

At least the latter had some fun in shareholder meetings. SBC is just plain, boring theft. Right?

There are certainly real issues with paying employees in stock. First and foremost, it may not be what it professes to be – a great way to ensure that employees are incentivised to perform to their best abilities over the long term. Psychologically, very few people have any tangible influence on their employer’s share price, and even for top level management a lot of factors are completely out of their control. Right now, Jerome Powell determines what the stock of most of our companies does tomorrow, far more than their respective leadership teams. And what happens in a bear market when share prices all fall by over 20% – do employees adjust their hours accordingly?

Far better, in this author’s opinion, would be to create an incentive structure that pays managers for excelling at their actual job – organic revenue growth and ROIC targets for top management, sales targets for the salesforce, etc. Personally, I feel much more confident with information provided by managers who are predominantly incentivised to run a business, rather than to juice the stock price.

However, today the discourse on SBC seems to have increasingly broadened into a feeling that something more insidious is happening. It’s not just that managers aren’t being optimally incentivised, but that companies are pulling the wool over investors’ eyes through nifty tricks like ‘adjusted EBITDA’, resulting in lofty share prices far exceeding their intrinsic value.

Figure 2: The discourse on SBC seems to have increasingly broadened into a feeling that something more insidious is happening

Does SBC Juice Company Valuations?

At Montanaro, we invest in many companies that use SBC as an incentive tool – indeed, with a tilt towards the technology and healthcare sectors it would be nigh on impossible to avoid doing so.

As it turns out, notwithstanding the endless heroic commentaries from vociferous portfolio managers with a saviour complex, SBC is nothing to be afraid of when valuing businesses.

There are two issues to consider – the impact on valuation from options granted in the past, and the impact from options that will likely be granted in the future. To account for historically granted options, we use the ‘fully diluted share count’, which must be reported by all companies. This is overly conservative (not all options will vest), but we like that.

To account for future options, we then forecast earnings including forecasted annual SBC expenses. Fortunately, companies have to value the options they issue each year using a horrible equation that won a big maths prize, so we can get a reasonable idea of the value of the options that have been earned by employees each year historically. Then we have a think and say: ‘well, probably these expenses will continue going forwards, and actually yes they’ll probably grow because SBC is cool’.

In fact, we are again being overly conservative here, because in reality employees generally have to pay something to receive their stock once it vests. We don’t credit companies for these payments in our valuations. Fine.

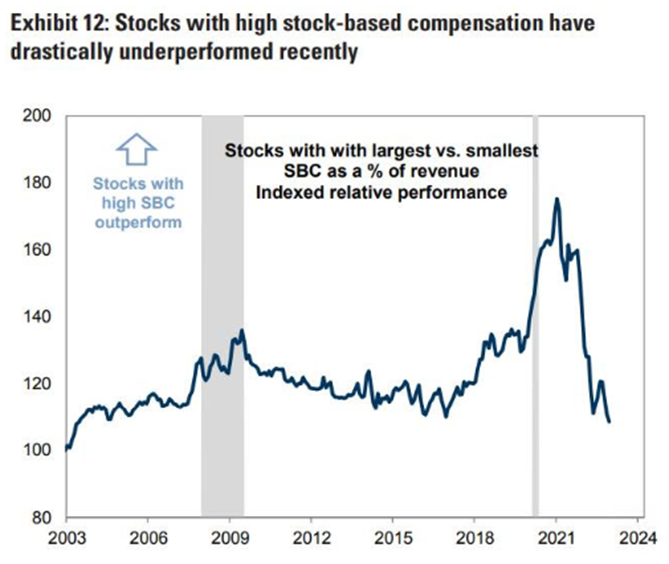

At this point it might assist my argument to produce a clever Bloomberg chart, elegantly proving that the share prices of companies that use SBC do just as well over the long term as those that don’t. In fact, I saw a chart the other day that showed that companies that pay SBC significantly outperformed since the mid-2010s, but then abruptly started underperforming in 2021. In all likelihood though, this simply reflects the relative performance of high growth tech (the sector where SBC is most in vogue) over this period.

Suffice it to say, valuing businesses that use SBC is really not that hard anymore. They solved it in 1973.

Figure 3: A clever chart elegantly proving the author wrong – maybe

Is Adjusted EBITDA Evil?

I’ve argued that SBC might not be all it’s cracked up to be in terms of an incentive tool, but likely isn’t something to get too worried about when it comes to valuing businesses.

This isn’t a popular view to put forward in an annual letter to shareholders in 2023.

***Yes, but tell them how much adjusted EBITDA sucks!***

Well, so long as you’re not putting adjusted EBITDA numbers in your valuation model, the information it contains can be informative.

As equity analysts, we are generally interested in trends – is the company having to spend more to grow at the same rate? Is its return on invested capital declining as a result?

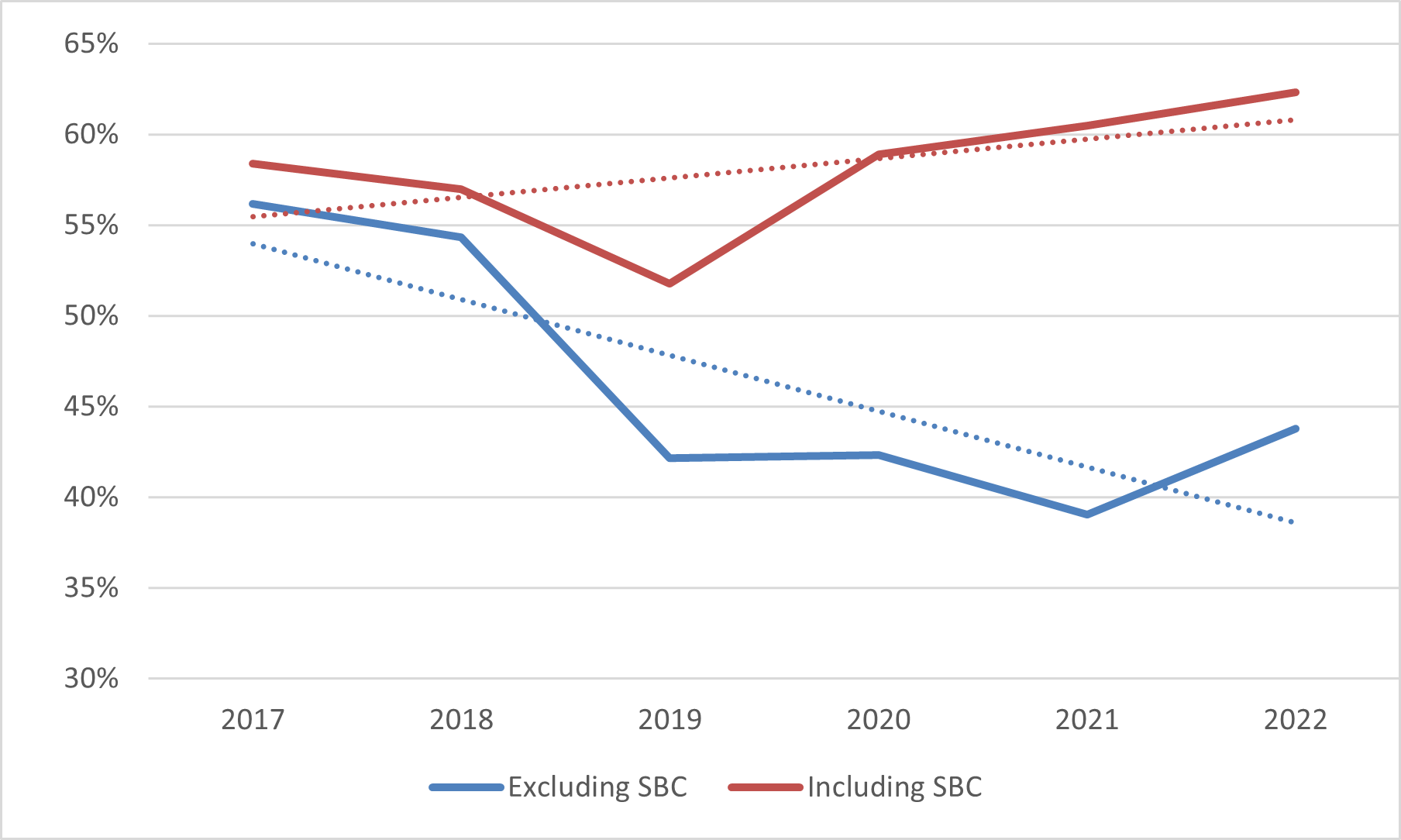

The way that SBC is valued by accountants can make such trend analysis difficult when looking at reported numbers, because the Black-Scholes-Merton equation used relies on several input assumptions, that can each change significantly from year to year. For example, interest rates and stock market volatility have both increased in recent months. This will mean that if a company issued its employees the exact same kind and number of options this year as it did last year, they will now record a larger expense. Trend analysis caput!

Again, for valuation purposes it is prudent to base our expense forecasts off the most recent year. But it is useful information to know that if these exogenous factors hadn’t changed, the company might have been able to post efficiency gains. At least it is a basis for a real, non-antagonistic, conversation with management.

Figure 4: Zscaler S&M Expenses as % Revenue – Could Accounting Assumption Changes be Masking Efficiency Gains

Action Points

In conclusion, we could probably do better than SBC when it comes to incentive tools. But don’t believe the hype when you read its use has led to a tech bubble. If you avoid all companies that pay significant levels of SBC, you will miss out on many great quality growth investment opportunities. Don’t be a rabbit.