ESG Ratings: Useful research tool or not fit for purpose?

The popularity of investment products that support the ethical or sustainability preferences of investors has accelerated in recent years. This has been well documented. Research by the Global Sustainable Investment Alliance (GSIA) indicated that investments made using strategies that incorporate ESG in some way had reached $35.3 trillion across five major markets in 2020. This represents a 15% increase in these types of assets under management between 2018 and 2020[1]. If growth continues at a similar pace, it is estimated that global ESG assets could exceed $53 trillion by 2025, over a third of global managed assets[2].

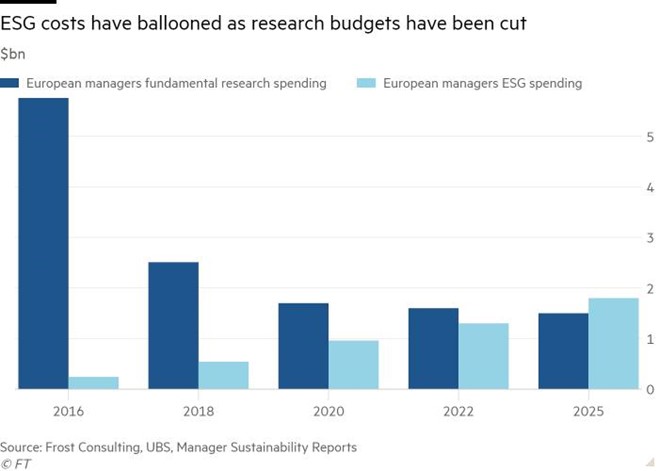

This surge in responsible investing has led to a boom in ESG product launches. However, the pace with which the asset management industry has taken up responsible investing has led to a knowledge gap amongst professionals. Analysts who have spent their careers conducting fundamental analysis in a particular way are now expected to integrate a huge range of non-financial information as part of their process. The learning curve has been steep and there has been a rise in demand for additional research resources from specialist ESG providers. To put this in perspective, it is expected that by 2025 European asset managers will be spending more on external ESG research than on traditional fundamental research.

So, it is not surprising that ESG ratings and database providers have suddenly shot to fame. Two dominant leaders have emerged: MSCI and Sustainalytics. These providers have different assessment methodologies but are often compared to one another.

Sustainalytics arrives at a final ESG score by calculating a company’s exposure to unmanaged ESG risk and categorising that risk from negligible to severe accordingly. The final risk classification is supposed to be absolute and comparable between industries.

However, MSCI identifies key issues on an industry-by-industry basis. Scores for individual companies are normalised across the industry in question and a letter-based system from AAA (best) to CCC (worst) is used to denote the overall ESG performance of a company. This means the MSCI scoring system is relative and designed to form a peer analysis.

| CCC | B | BB | BBB | A | AA | AAA |

Both methodologies involve materiality assessments, and this is often where subjectivity lies. It means that, not only are different scoring systems used, but the selection of the most pertinent ESG factors affecting each company and/or industry could be completely different. This is one of the criticisms that ratings agencies often face: a lack of correlation. A 2018 study[3] found a correlation of 0.3 between providers. This low agreement between important research houses can lead to confusion as to how investors should interpret the conclusions.

The sourcing of the underlying data can also lead to problems with scoring. The ESG data used to generate the final rating comes from the company themselves. Despite the increasing regulatory pressure to standardise corporate ESG information, the verification process can still prove problematic. This has led to some ESG Ratings that have raised eyebrows in the past.

Case Study 1: Boohoo – MSCI Rating A (downgraded from AA in 2020). (Montanaro have never invested in Boohoo across any of our Funds[4]).

In the summer of 2020, an undercover report in The Times found that garment workers in a Leicester factory supplying to Boohoo were being exploited[5]. The suppliers failed to provide safe working conditions and were paying staff below minimum wage. The revelations in the article and resulting scandal led MSCI to downgrade their rating from AA to A. However, two questions were still at the forefront of investors’ minds:

- Why was the score so high in the first place?

When the risk assessment for supply chain management was undertaken, MSCI used the geographical location of the majority of Boohoo’s tier one suppliers to determine the likelihood of human rights abuses. It was determined that, due to the low reliance on supply chains in regions with poor working conditions, the exposure to supply chain management risks was sufficiently low that the final rating should not be negatively influenced to any large degree. This is an example of how materiality assessments can be flawed.

Boohoo also did not publish supplier locations or conduct supplier mapping in the UK in 2020. Additionally, in the aftermath of the controversy, Boohoo stated that the supplier involved was not declared. It is difficult to know how the publication of this additional, relevant information could have affected the MSCI analysis, but it serves to highlight how the reliance on company transparency surrounding sensitive issues can lead to improper calculation of risk.

- Why has the score remained fairly high despite shocking discoveries of labour rights abuses?

MSCI categorise this exploitation of workers as a “moderate controversy” and, whilst it has resulted in a downward revision of their headline rating, the company is still considered to be ahead of the majority of peers using their normalisation methodology. This dissonance between the MSCI reaction and that of the public at large has caused some to scratch their heads. It means that investment products that rely solely on MSCI ratings for their ESG analysis could hold companies like Boohoo, despite them still being dogged with allegations of labour violations[6].

The example above also highlights a further criticism of some rating methodologies: the use of relative scoring for peers means that goalposts shift between industries, limiting comparability. The result is that certain companies may score well simply because they are the “best of a bad bunch”. We have seen evidence of this amongst the Montanaro Approved List. Companies within sectors where ESG disclosure is poor may end up with inflated ratings when compared with companies in sectors with better levels of reporting. For example, a company that operates in the renewable energy space may have a much lower score than an industrial company but how much this tells us about the difference in ESG risk exposure between the two is limited.

Case Study 2: Exxon Mobil – One of the largest constituents of the S&P 500 ESG Index (as at 29th April 2022). (Montanaro have never invested in Exxon across any of our Funds).

The inclusion of the oil giant within the S&P 500 ESG Index led to tough questions being asked of the S&P ESG assessment process. Not least from Tesla CEO, Elon Musk, as the most recent rebalance of the index saw Tesla removed on the basis of a downgraded S&P DJI ESG Score. These changes were designed to bring about “meaningful and measurable sustainability-focused enhancements.”[7] The scores focused on reporting rather than the products and services of the company and as a consequence the ESG risks for Tesla were thought to be higher than for Exxon.

The construction of the index uses the S&P DJI ESG Scoring system alongside exclusions of specific business activities that are determined by Sustainalytics. These exclusion criteria do not apply to all oil and gas companies, which is why Exxon Mobil can be included in the S&P ESG Index series[8]. However, the removal of an electric vehicle company (despite valid governance concerns) and inclusion of an energy giant leads to legitimate criticisms of how well the methodology applied here truly reflects the needs of responsible investors.

High profile detractors like Musk, who are able to use their platform and act in the interest of their companies by speaking up against the ratings system, can lead to widespread criticism, not just of particular ratings or research, but of responsible investing as a whole. It gives the impression that ESG considerations can sometimes mean we can’t see the wood for the trees and focus too heavily on reporting and tick box exercises rather than common sense reviews of how a company’s core output contributes to the transition to a low carbon economy.

It is for these reasons that we at Montanaro have always applied a proprietary process for assessing ESG risks and opportunities. We make use of our own ESG checklists to inform our analysis of a company’s quality as part of our investment process.

What are the positives?

The size of the databases offered by large ESG research houses means that these agencies offer valuable information on important ESG metrics (such as carbon, waste, and water intensities).

It is for this reason that Montanaro subscribe to the MSCI database. We receive environmental data on investee companies and the wider index. This data is then incorporated into our ESG Checklists, allowing us to better understand the ESG profile of the businesses in which we invest.

It is also important to note that MSCI’s mission is to enable investors to build better portfolios for a better world. MSCI is a leading provider of critical decision support tools and solutions for the global investment community. It helps investors address the challenges of a transforming investment landscape and power better investment decisions. Increasingly, MSCI is developing products to help investors seeking to build sustainable and ESG focused investment products in line with new regulation and meet climate requirements. In addition, the methodologies of both MSCI and Sustainalytics are regularly adapted to help tackle issues with corporate transparency and the reliance on this reporting to evaluate ESG risks. Both have sought to include additional alternative data to supplement company reporting. For example, MSCI have incorporated flood maps to identify where company operations are more exposed to the physical risks of climate change even when the company themselves may not disclose this[9].

More capital needs to be directed towards sustainable businesses to address social and environmental challenges. The services offered by research providers are helping to drive capital towards sustainable areas of the economy via the provision of increased data and the pressure their ESG research (however flawed) puts on companies to improve standards.

As well as the pressure to invest responsibly and the need to transition to a low carbon economy, an increased regulatory burden is also presenting challenges to the investment community. The introduction of new regulation, such as the Sustainable Finance Directive Regulation (SFDR) in the EU, means that services such as those provided by MSCI will be needed to aid asset managers to comply.

Conclusion

Rating and research agencies can play an important role in providing key information to investors. Their vast databases can be used to help make better investment decisions and manage ESG risks that have historically been externalised[10]. However, a blind reliance on a single score from external research houses can lead to reputational damage for those who don’t apply their own proprietary responsible investing processes to sense-check the output. The information from ESG research houses should be seen as one tool in the ESG assessment arsenal rather than the be all and end all of ESG analysis.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author at the date of publication and not necessarily those of Montanaro Asset Management Ltd. The information contained in this document is intended for the use of professional and institutional investors only. It is for background purposes only, is not to be relied upon by any recipient, and is subject to material updating, revision and amendment and no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made, and no liability whatsoever is accepted in relation thereto. This memorandum does not constitute investment advice, offer, invitation, solicitation, or recommendation to issue, acquire, sell or arrange any transaction in any securities. References to the outlook for markets are intended simply to help investors with their thinking about markets and the multiple possible outcomes. Investors should always consult their advisers before investing. The information and opinions contained in this article are subject to change without notice.

[1] http://www.gsi-alliance.org/

[2] https://www.bloomberg.com/professional/blog/esg-assets-may-hit-53-trillion-by-2025-a-third-of-global-aum/

[3] Krosinsky, C. (2018) The Failure of Fund Sustainability Ratings

[4] https://www.ft.com/content/ead7daea-0457-4a0d-9175-93452f0878ec

[5] https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/boohoos-sweatshop-suppliers-they-only-exploit-us-they-make-huge-profits-and-pay-us-peanuts-lwj7d8fg2

[6] https://www.business-humanrights.org/en/latest-news/uk-study-finds-over-half-of-leicester-garment-workers-face-continued-labour-violations-two-years-after-pandemic-revelations-on-working-conditions-incl-below-minimum-wage-pay/

[7] https://www.indexologyblog.com/2022/05/17/the-rebalancing-act-of-the-sp-500-esg-index/

[8] https://www.spglobal.com/spdji/en/documents/methodologies/methodology-sp-esg-index-series.pdf

[9] https://www.msci.com/www/blog-posts/using-alternative-data-to-spot/01516155636

[10] https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1086026619831451