Do the Himba believe in Climate Change?

In April 2018, Mr M. went to Siberia to ask the Nenet about Climate Change (see blog) writing: “My long-suffering wife is getting weary of holidays where the hottest part of the day is minus 30 degrees, the loo consists of a hole in six feet of snow with a shovel and a wash comes from baby wipes and clothes are never removed. Can’t understand the problem personally…”

Wind the clock forward … a trek to West Papua in November 2019 … then a Covid enforced interlude (couldn’t risk wiping out a remote indigenous tribe) … and it was time to get back in the saddle and to explore once again. Where to this time? Having travelled the Amazon and remote jungles in West Papua, it was time for somewhere new … Africa.

A few weeks ago, my wife is still long suffering and even more weary of these “holidays”, but this time the hottest part of the day was over 45 degrees (yes, it was a tad hot); the loo was a long drop (but look on the bright side, no need for a shovel); there was no water at all to wash – so once again, thank goodness for baby wipes (still had some left over, more good news); and clothes were removed at night but couldn’t be washed, so our back pack filled daily with dirty washing; temperatures drop to just above freezing at night, so Mrs M. shivered in a sleeping bag at three o’ clock each morning until the pesky cockerels woke us up; … still can’t see the problem with my holidays …

We visited a Himba village in north-western Namibia close to the Angola border. Each village consists of a single extended family. It took three full days to reach so few (if any) tourists had visited before let alone actually lived with them. It was a first. We were not expected, so on arrival our guide had to seek permission of the chief for us to stay which he gave. He liked having his picture taken.

We were off grid: no mobile phone signal; no electricity or power of any sort; no running water (so no way of washing) and no loos…

We were off grid: no mobile phone signal; no electricity or power of any sort; no running water (so no way of washing) and no loos…

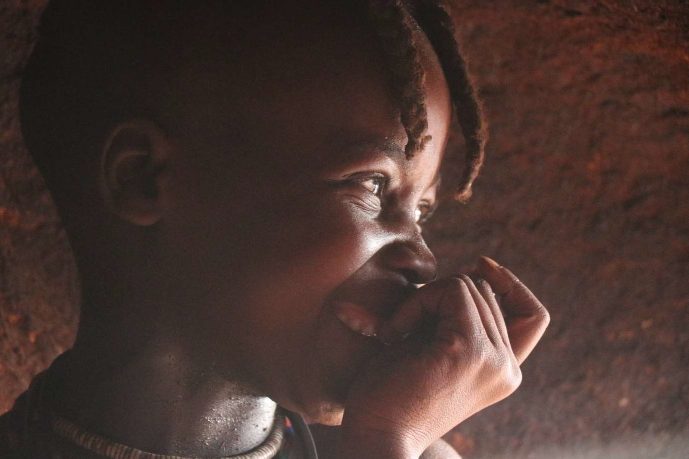

The Himba continue to live a traditional life: the women wear next to nothing (loin cloths and jewellery) and each day cover their whole bodies with clay and cattle dung mixed with red ochre. This gives them a remarkable dark red colour and protection from the blistering sun. They braid their hair with red ochre paste too and take great pride in their appearance and love their children. When it is too hot to venture outside their huts, broadly from noon until five, they take it in turns to groom each other to look beautiful as they did while we hid in any shade that we could find.

When it is too hot to venture outside their huts, broadly from noon until five, they take it in turns to groom each other to look beautiful as they did while we hid in any shade that we could find. Women are allowed to wash with water on only one occasion, immediately after giving birth. Instead, they prepare incense made of aromatic herbs and resins that smell nice. Inside a hut it is very, very smoky.

Women are allowed to wash with water on only one occasion, immediately after giving birth. Instead, they prepare incense made of aromatic herbs and resins that smell nice. Inside a hut it is very, very smoky.

They are nomadic pastoralists who survive by herding cattle and moving them daily to find grazing and water. This is the job for the men who are away from the village most of the time, so the village largely consisted of women, children and babies. Each day the women collect firewood, milk the goats, prepare meals and in the evening collect water: Ever the gentleman, Mr M. thought of offering to carry the ten gallon can of water – but could barely lift it… They also herd goats and take the kids to the village at night for protection against hyenas and other predators.

Ever the gentleman, Mr M. thought of offering to carry the ten gallon can of water – but could barely lift it… They also herd goats and take the kids to the village at night for protection against hyenas and other predators. They are very proud of their culture and traditions which continue largely unchanged. At the age of ten, parents offer their daughters in marriage to an appropriate arranged match. Most men have at least two wives (if they have enough cattle). As children, young girls have braids that cover their faces like a veil.

They are very proud of their culture and traditions which continue largely unchanged. At the age of ten, parents offer their daughters in marriage to an appropriate arranged match. Most men have at least two wives (if they have enough cattle). As children, young girls have braids that cover their faces like a veil.

At puberty, the men are circumcised and the young women have the bottom four front teeth knocked out to look even more beautiful. Many chisel the two top incisors into a point. Decided not to go native this time …

At puberty, the men are circumcised and the young women have the bottom four front teeth knocked out to look even more beautiful. Many chisel the two top incisors into a point. Decided not to go native this time …

One tradition intrigued whilst researching and organising the trek: it is customary for the chief to offer one of his wives to a male guest to sleep with at night if invited to stay. Well, suffice it to say, it seemed a good idea to tell Mrs M. in advance – it did not go down well. Before you ask, there was no suggestion that I could find that the chief expected to receive the guest’s wife in return. When the chief finally agreed that we could stay, he very formally said to me “this is now your village”. Both Mr M. and Mrs M. exchanged glances wondering if there was a subtle message implied… (there wasn’t).

Would have been tricky to explain to Mrs M….

The Himba believe that everything that happens to them in their lives is down to their God Mukuru. The chief prepares a holy fire which he tends each evening and is constantly smoking. It is positioned in a line between the gate of the coral, where the animals stay at night and the entrance to the chief’s round hut (made of mud and clay). It is a cardinal sin and the ultimate faux pas to walk between the coral and the holy fire. We were super careful not to offend. The Himba believe that the smoke from the fire rises and reaches their ancestors in the sky who then intermediate on their behalf with Mukuru.

It is a cardinal sin and the ultimate faux pas to walk between the coral and the holy fire. We were super careful not to offend. The Himba believe that the smoke from the fire rises and reaches their ancestors in the sky who then intermediate on their behalf with Mukuru.

Wealth and status come from cattle. The larger the herd the higher the position within the community. To marry one or more women, a bride wealth is agreed – an ox is the minimum along with cattle of good quality – and they offer shells worn as a necklace (we brought some with us which went down well).

The Himba live in a tough environment. The sun shines more than 300 days a year reaching temperatures well above 45 degrees. The rainy season starts in November when the semi-desert riverbanks briefly flood. But it is still very hot and the water evaporates quickly. All the trees we saw looked dead without leaves – shade is hard to find – yet briefly, we were told, in the rainy season they turn to green.

So, do the Himba believe in climate change? This is what the chief told us: “Omatanaukiro womuinjo we vaverua jetutuna tjinene tjimuna omarokero wombura nga tanauka ngeheri tjimuna ozombura omirongo vivari nda kapita. Ovinamuinjo vikoka tjinene mena rokutja omuinjo wevaverua watanauka kukara oupju nourumbu tjinene.” For those whose Himba is a little rusty: “Climate change has affected us very badly. It no longer rains as it used to rain 20 years ago. Our livestock that give us life to live are dying. It is always hot and dry.”

They told us that twenty years ago their village that is now dry, brown and dusty would have been green with grass and flowering trees. The rainy season is now shorter and unpredictable. They have experienced droughts as never before: in 2012, they suffered a drought that lasted seven long years.

We were told of a chief who had 1,000 cattle before the drought began who lost over 90% of his herd. Cattle could be seen dead or dying lining the paths where they walked desperately looking for water. The chief became a pauper (rather like the story of the Nenet). Just when the rains finally arrived in 2019, then along came Covid! Mukuru really was must have been cheesed off with

the Himba…

The Himba say, “water is life”. Climate change means that water is now harder and harder to find. They have to dig in the sand with their bare hands to find any water to drink and to water their cattle. They pass the water up in a bucket for the chief to then give to the cattle. They seemed to know when it was their turn to drink and waited patiently. But they are only led to the water hole every other day. There is simply not enough water.

They pass the water up in a bucket for the chief to then give to the cattle. They seemed to know when it was their turn to drink and waited patiently. But they are only led to the water hole every other day. There is simply not enough water. Remarkably, despite a tough life that few could imagine, the Himba are one of the warmest, friendliest and most humorous people to have ever welcomed us into their lives. Anyone who would like to learn more should read “The Place of Stunted Ironwood Trees” by David Crandall.

Remarkably, despite a tough life that few could imagine, the Himba are one of the warmest, friendliest and most humorous people to have ever welcomed us into their lives. Anyone who would like to learn more should read “The Place of Stunted Ironwood Trees” by David Crandall.

The Himba are amazing. We returned, as always, truly humbled.

Mr and Mrs M. (10 November 2023)