Biodiversity – The Next Big Challenge

Montanaro have selected a new charity to support, Rewilding Britain[1]. The charity restores ecosystems to allow cycles and systems to re-establish. Their aim is to get to the point where nature can take care of itself. They want to move away from protection as the main model of supporting the natural environment of Britain to recovery and restoration.

As well as our philanthropic support of causes that champion biodiversity, we are attempting to incorporate ecological considerations into our investment process to a greater extent. We want to understand the challenges surrounding the measurement and protection of biodiversity, as well as how investors can encourage businesses to be better stewards of the biosphere.

What is Biodiversity?

Biodiversity is the term used to describe the number and variety of organisms in a region. This means plants, animals, fungi… if it’s alive, it’s contributing to the richness and resilience of life on Earth. And it’s declining at an alarming rate. This reduction in the variety of life is thought to be the planet’s sixth mass extinction event (and it’s accelerating). A mass extinction event is when species vanish much faster than they are replaced. This is usually defined as about 75% of the world’s species being lost in a short amount of geological time. Five previous mass extinctions have changed the face of life on Earth. The present event has been dubbed the “Holocene extinction”.

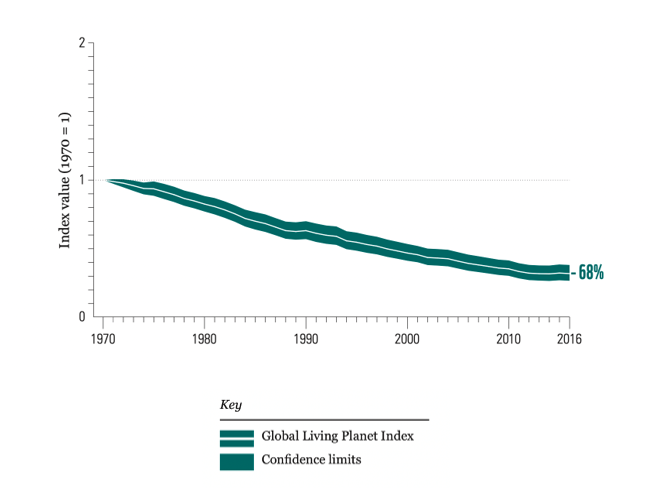

The chart above shows the Living Planet Index (developed by WWF in conjunction with the London Zoological Society) which tracks the abundance of almost 21,000 populations of mammals, birds, fish, reptiles, and amphibians around the world and indicates an average 68% decline in their monitored animal populations[2].

Despite this, it is a topic that often goes largely unmentioned in corporate sustainability reporting. During a recent conversation with the Head of Research at Impact Cubed, Antti Savilaakso, we discussed the reasons for this. One of the key challenges is the lack of a standardised unit of measurement. Investors like things that can be measured, quantified, and compared. Biodiversity cannot be manufactured and understanding how companies can enhance the natural environment can be highly dependent upon the local ecosystem and type of industry. In comparison, setting Net Zero emissions targets appears to be pretty straightforward – there is a common, quantifiable goal irrespective of industry or geography. The concept of “net nature positive” is far more nebulous.

What is being done?

Although these hurdles are challenging, efforts are being made to establish a common model of best practice. One of the reasons why this year has been a particularly important one to explore biodiversity is the development of the TNFD (Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures). This new framework is modelled on the existing TCFD (Taskforce on Climate-related Financial Disclosures). Both frameworks aim to standardise corporate reporting on environmental issues. The TCFD is already well established, and the UK Government has introduced mandatory reporting against this framework for some businesses. The TNFD aims to use the momentum of this reporting framework to expand the scope beyond climate change and encompass wider ecological metrics. We have participated in consultations with the TNFD to reflect how we think new disclosure requirements should be developed. We’re hopeful that TNFD will aid businesses in assessing their impact on complex natural systems in a meaningful way.

In addition to corporate disclosure frameworks, the international community is coming together this year (following a COVID induced hiatus) to discuss the next decade for biodiversity action planning. The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) is a global agreement that aims to bring the world together under a ten-year plan to reverse the loss of biodiversity. It is an important summit that has its own Conference of the Parties (COP) – the first of which was held in Nassau, in the Bahamas, in 1994. Confusingly similar to the recent COP26 held in Glasgow, the conferences are separate. How the latest COP on Biodiversity – COP15 – aims to improve the world’s biodiversity will have repercussions on how the international community deals with climate change. These conferences allow decisions to be made between countries for the benefit of all people and the planet. These decisions can guide, and shape national and local action taken for nature.

At the 2010 meeting of the CBD, countries agreed to a set of 20 global targets which aimed to halt biodiversity loss. These came to an end in 2020 and few of the targets were actually achieved by the countries involved, including the UK. There are a number of COP15 conferences taking place this year, the most recent finished at the end of June in Nairobi. The focus is the development of a post-2020 action plan on biodiversity and will conclude in Canada this December. The new targets will range from addressing species extinctions and recovering populations, to reforming unsustainable extractive industries and tackling pollution. Alongside these targets, the money to deliver them, and the methods of monitoring progress are also being discussed. This new framework will be adopted at CBD COP15 but so far little has been agreed upon. As with COP26, achieving a meaningful agreement between the participating countries and balancing their interests is proving to be no small feat[3].

At a national level, HM Treasury commissioned a review of how a prosperous society is reliant on the natural world. “The Economics of Biodiversity” (or The Dasgupta Review) outlines the relationship between ecosystems and our economy. This review calls for a shift in the way we view the assets nature provides and warns of the dire consequences of overexploitation. Since its publication, it is already informing future policy action and will likely influence the approach taken to biodiversity in the UK[4].

Regulatory pressures are already being exerted elsewhere. In the EU an action plan has been developed on sustainable finance. An important part of this plan is the introduction of the EU Taxonomy which attempts to define “green activities” for the first time. The idea is to tackle the phenomenon of “greenwashing” (overstating or misrepresenting sustainability credentials of a business) by defining commonly used criteria that economic activities should comply with in order to be considered environmentally sustainable. Business activities must contribute to at least one of the six environmental objectives that have been decided upon; this includes protecting or restoring biodiversity and ecosystems. The EU regulators are still in the process of ironing out the details of what type of operations can be considered meaningful contributors to this theme, but the introduction of this regulation is helping to push biodiversity and ecosystems further up the business agenda[5].

Although this regulation is still in development, some European countries are already acting on these requirements. France has been at the vanguard and introduced a decree that will require French investment firms to undertake biodiversity reporting. The lack of biodiversity data is raising eyebrows about just how financial institutions will comply with this decree. This is why frameworks like the TNFD are desperately needed to ensure consistency in reporting and establish a best practice standard[6].

With all these advances in how policymakers and investors are considering humanity’s place in nature, we’re confident that businesses will be forced to consider the impact of their activities on biodiversity sooner rather than later. This is why Montanaro’s Investment Team is conducting a research Deep Dive on the topic. We want to speak to researchers, charities, and companies to establish where we are now and what we collectively want and should aim to achieve. We hope the findings will influence how we incorporate biodiversity risks into our ESG and engagement strategies in the future.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author at the date of publication and not necessarily those of Montanaro Asset Management Ltd. The information contained in this document is intended for the use of professional and institutional investors only. It is for background purposes only, is not to be relied upon by any recipient, and is subject to material updating, revision and amendment and no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made, and no liability whatsoever is accepted in relation thereto. This memorandum does not constitute investment advice, offer, invitation, solicitation, or recommendation to issue, acquire, sell or arrange any transaction in any securities. References to the outlook for markets are intended simply to help investors with their thinking about markets and the multiple possible outcomes. Investors should always consult their advisers before investing. The information and opinions contained in this article are subject to change without notice.

[1] https://www.rewildingbritain.org.uk/

[2] https://livingplanet.panda.org/en-gb/

[3] https://rspb.org.uk/our-work/rspb-news/rspb-news-stories/what-is-cop15/?from=morelikethiscop

[4] https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-economics-of-biodiversity-the-dasgupta-review-government-response

[5] https://www.nossadata.com/blog/sfdr

[6] https://tnfd.global/news/frances-article-29-biodiversity-disclosure-requirements-sign-of-whats-to-come/