Inflation Anxiety: Much Ado About Nothing?

Inflation! Supply Chain! Chip shortage! Doughnut shortage! Rates!

There’s a lot going on in the markets, and our style is not to make macroeconomic-driven stock selection or portfolio management decisions for the reasons best articulated by Simon Evan-Cook’s recent article ‘busting the 90% asset allocation myth’: namely, that they can be (asymmetrically) value-destructive, and even more importantly, that asset allocation and strategic allocation decisions are decisions that the client makes. In our case, we offer our clients full exposure to Quality Growth Equities. To tinker with that would be dishonest and unhelpful.

But as they say – no man is an island – and so too, no company is an island: we are interested in some of these topics and what they might mean for our individual companies’ prospects. And more than that, we are struggling to see the doom and gloom being painted by some headlines, particularly around inflation and supply shortages. Here are some thoughts to hopefully alleviate some of that inflation anxiety.

Inflation: Shouldn’t we be seeing more?

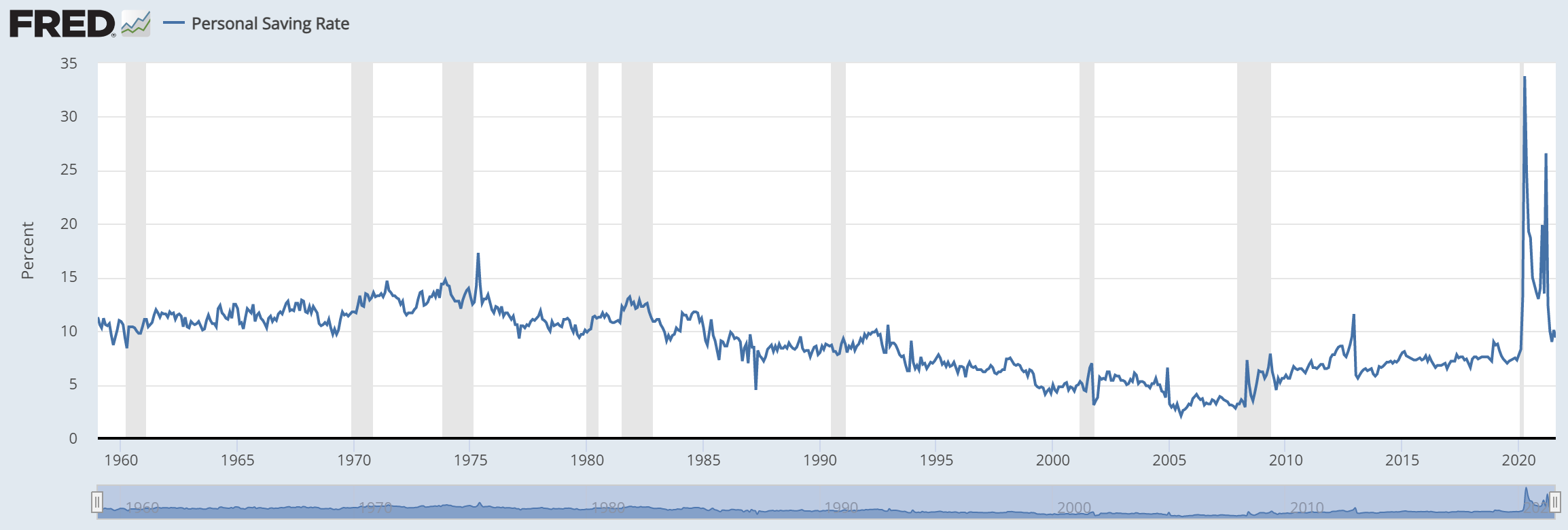

Those banging the inflation drum might want to consider that we are exiting the greatest overnight global supply shock in global economic history (Covid19 synchronized global lockdowns), with the most acute burst of short term demand in the last hundred years (the savings rate got to nearly 35% last year – the highest ever), and overlayed with huge supply-chain bottlenecks…

…Surely in any other circumstance this is a perfect storm for the most record-breaking inflation on record?

And yet what we find surprising is just how calmly this is passing through, which likely points to underlying structurally deflationary pressures (the deflationary effects of innovation, globalization, and technological creative destruction are among them).

So let’s put these ideas into context.

We had the highest Savings Rate spike on record (all the data that follows relates to the US, but the numbers for Europe are comparable).

This is a proxy for pent-up demand, and for the first time since the Second World War, it was globally synchronized, and it was unleashed after the reopening of a globally synchronized shut-down.

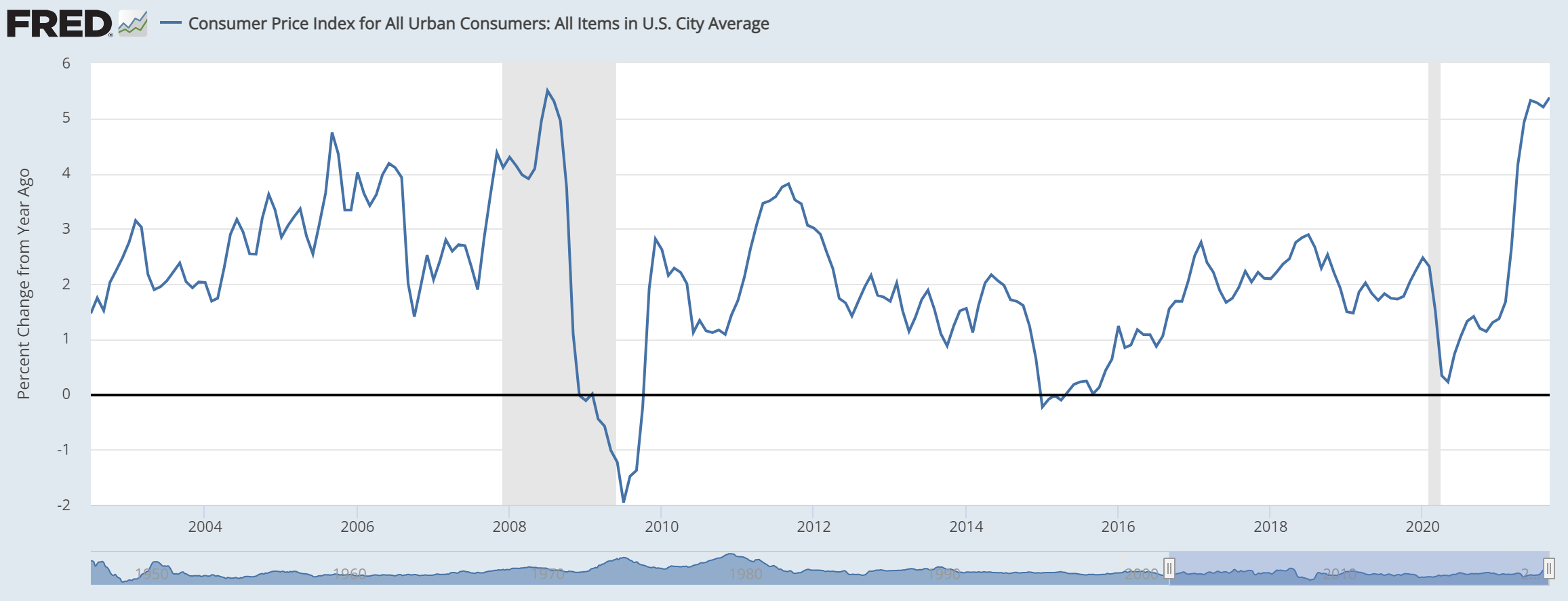

This has of course led to some inflation, which apparently is the focus of considerable angst:

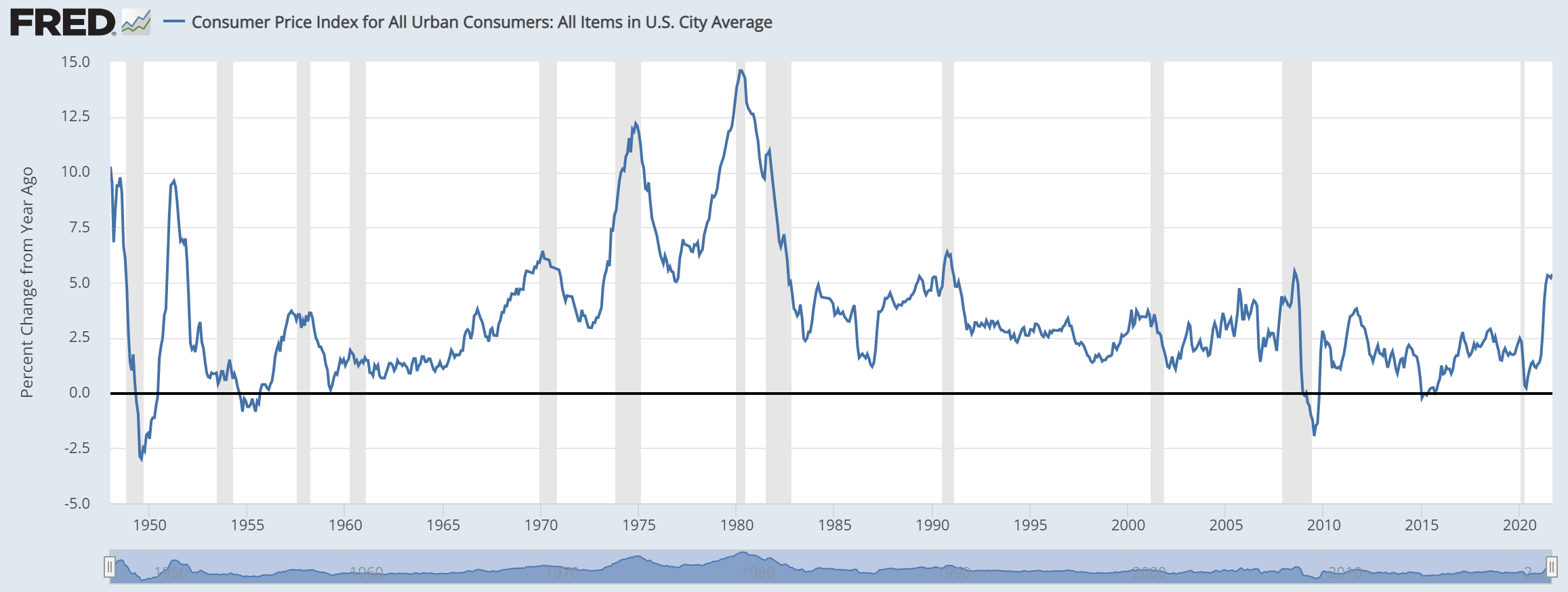

But inflation is an output. What’s the input? The input in this case is the savings rate translating into record-breaking demand being unleashed at once. In the context of that input, should the inflation rate not look more like this?

Why, then, is the CPI not well into the double digits? Isn’t this the real headline?

The last comparable global supply-shock followed by demand-flush was the end of the Second World War, and inflation reached 10% then. We’re not even close now.

Perhaps a useful thought experiment might be: what would the inflation rate be if Covid happened 50 years ago?

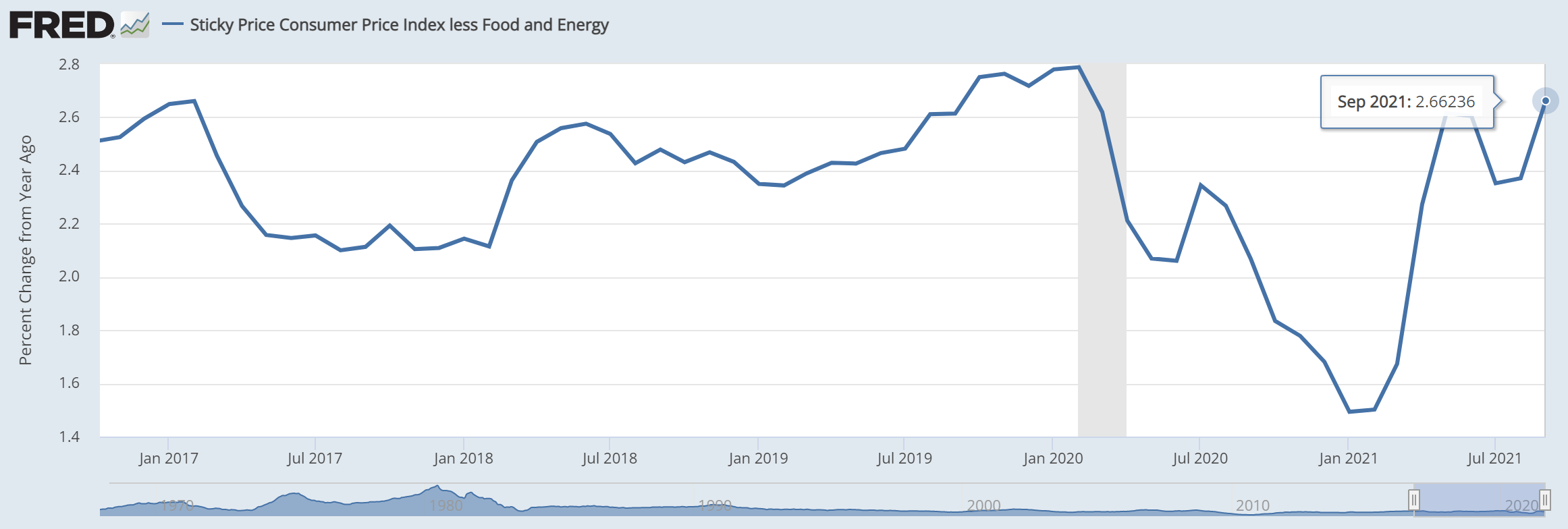

Moreover, if we look at the measure of the ‘sticky CPI less Food and Energy’ which counts only the basket of goods and services whose prices fluctuate with less volatility, we see that this metric is not even at its pre-pandemic level.

Doesn’t seem so doom and gloom…

Short Term Deflation and Supply Shortages to Loosen?

After the savings rate peaked last year, consumers went on spending binges that disproportionately went on goods over services.

Why? Because services were closed in lockdown! So durable and non-durable goods were the only thing to spend on, and thanks to the maturity of the e-commerce ecosystem, they could.

Now what’s happened? The economy is open again, travel is back, and spending on services is therefore back. So consumers should be rotating back into services, and demand for goods should normalize below its current fizzy peak.

The issue is that a lot of goods-producing companies have likely got into a panic to catch up with the unprecedented demand for goods (we see this with the chip shortage, now that chips have made it beyond their traditional homes in computers and into more mundane household items like fridges), and extrapolated forward the consumer’s demand. There is a good chance this has led to over-ordering – double ordering and triple ordering from large goods producers, which has added fuel to the fire of the chip shortage and other input material shortages – but will soon be met with the reality over the next 6 to 12 months that demand for goods has waned to more normal levels.

If this happens, many companies will be left holding a glut of inventory, and it is entirely reasonably to imagine prices being cut to move some of this stock.

Somewhat contrary to the narrative, therefore, we can see cyclical deflationary pressure percolating through the economy next year.

An article for another time will explore the technological and innovation-related forces that are keeping a lid on prices (these range from creative destruction, to supply-side expansion, and increased competition from lower barriers to entry); but until then, those who doubt the structurally deflationary impact of innovation may wish to ask themselves why in a decade of loose money and rock bottom interest rates, central banks couldn’t hit their 2% target, despite the economy at full employment….

Autos and Semis

On the autos side, we saw the sharpest V-shape demand recovery, with consumers buying cars at a record-setting pace (compared to any other time post crisis) in H2 2020 and H1 2021. Now, while there is a chip shortage in some areas, this may well be disguising a fundamental normalization of demand, at least in autos.

Besides – it’s not as if the chip shortage is totally prohibitive to growth. Look at Tesla. That Ford and GM are selling fewer cars is most certainly down to a normalization in demand after a fizzy spike.

According to ARK’s Cathie Wood, April saw 18.5m cars sold in the US – and this has come crashing down to 12.3m cars sold in September – a near recession-like deceleration. Given the amount of double and triple-ordering by autos OEMs I struggle to put all of this down to chip constraints. If Tesla can grow, GM should be able to grow, but GM didn’t grow…there may be something else at play here beyond the ‘chip shortage’. One clear element is overbuying before, and another may be that each and every consumer entering a car replacement cycle might be struggling to justify the capex on an internal combustion engine car, which can no longer be depreciated over 20 years, and sold second hand after 10. Who would buy a combustion engine car in 10 years? Will that even be legal?

In any case, GM, Ford and Tesla are all indicating that the chip shortage is improving for autos and instead of panicking about it, we are thinking about what it might mean for our companies if the chip shortage is resolved sooner than expected.

Long Term Chip Shortage or Surplus?

One thing we also need to make clear with all this hysteria about chip shortages is that in the grand scheme of things, to be pessimistic on this topic is to miss the wood for the trees.

What is happening is that chips are becoming more globally significant as they proliferate through the wider goods economy; Covid taught us their importance not only economically, but also strategically and geopolitically; and so since the pandemic most major chip makers and economies have accelerated efforts to radically increase domestic chip manufacturing capacity.

I’m not just referring to the capex plans of Intel and TSMC – look at countries like Korea which has announced a $450bn package to transform its chip production capabilities. One should also note the track record of companies like Samsung of moving quickly in tech land. So a lot of supply will be turned on in the next two years.

So far from any medium term chip shortage, we could quite plausibly have a capacity surplus in the mid-term.

EVs and Oil

Perhaps one of the reasons demand has fallen off for autos is because most reasonable middle class people whose car replacement cycle is coming up are pausing to consider EVs for the first time.

The shift to EVs is happening much faster than people expected, and I struggle to see a case where EVs don’t outsell non EVs in the next two years, for the reasons I mentioned earlier.

Even the forecasters like BNEF, who are always wrong (meaning they always underestimate the speed of change), are forecasting that EVs will make up the majority of new vehicle sales by around 2030. All this means that global demand for oil has peaked.

Oil’s importance in the global economy is declining so fast that even as we are seeing synchronized global economic growth, with every country coming out of a global supply shock roughly at the same time, global oil demand is still below its 2019 peak of over 100m barrels a day ! If in 2021 – in spite of lockdown exits globally – we still can’t get to over 100m barrels a day – you can see that this becomes another stranded asset in a few years.

If the world coming out of lockdown couldn’t get the oil price to record highs, what can?

This is not to say that oil prices won’t surge up in the mid-term (who knows!). Short term volatility should be expected in a dying asset class where capex investment are waning (it is becoming prohibitively expensive for oil companies to find and extract new sources of oil given the shape of the 10-year demand curve).

But in the long term, expect the price of oil to be deflationary. And of course I won’t waste time explaining why the long term prices of renewables will be deflationary (prices of anything are set by supply and demand, and the tautological raison d’être of renewables is to have limitless supply).

Unemployment and wage inflation

Another thing that’s noteworthy is that employment hasn’t quite recovered as quickly as anticipated. At 4.8%, we’re still way above the 3.5% number pre-Covid.

We had discussed internally back in April 2020 that the services sector would make such huge efficiency and productivity gains during Covid (from migrating to the cloud, buying more packaged software, modernizing communications like Zoom, etc), and additionally by management teams going through their opex spending line by line to find efficiencies, that most services companies would emerge into 2021 with better margins – reluctant to go back – and with a newfound realization that their PnLs had long been bloated with too many people.

Whether or not that is the reason we are not yet back to full employment, we cannot say, but it does make a great deal of sense from what many of the CFOs we speak to are telling us.

This may help put a lid on wage inflation in parts of the economy, given lower employee bargaining power.

Employees working from home more and migrating away from urban centres to cheaper areas may also lower employee bargaining power and should add to the downward pressure on wage inflation.

All of this comes together to suggest that so too when it comes to fears about spiralling wage inflation – we also don’t see any reason to panic.

By and large, whether or not inflation persists for a while, or whether it normalizes in the coming 6-12 months, our smaller companies can weather this storm because they are nimble enough, have enough pricing power, and are less exposed to commodity cycles and supply chains than most of the larger companies one finds in large cap land. Especially large cap value land!